The Rational Framework of Hadith Criticism

A Summarized Translation of Al-Sharīf Ḥātim al-ʿAwnī’s Al-Usus al-ʿAqliyyah li-ʿIlm Naqd al-Sunnah al-Nabawiyyah (The Rational Foundations Underlying the Science of Hadith Criticism)1

Basil Farooq

Translator’s Preface:

Students of hadith are intimately familiar with the five conditions of an authenticated (ṣaḥīḥ) hadith. The treasure troves of works on hadith criticism are focused on parsing and understanding these five conditions: discussing what the conditions are, understanding differences of opinion, listing exceptions, and demonstrating applications of these conditions to actual hadith. Rarely, if ever, is there an understanding of the objectivity and rationality underlying these five conditions. In the context of modernity and post-modernity, students of knowledge are required to have a deep understanding, not only of the topics and discussions within a science itself, but also the meta-aspects of these sciences. Clues to these meta-discussions are often found scattered throughout the works of the early scholars; however, the holistic presentation and synthesis of these underlying assumptions and principles in the form of a methodological framework is something that requires contribution from contemporary researchers. In this short work, Al-Sharīf Ḥātim al-ʿAwnī presents the logical and methodological framework of the science of hadith criticism (ʿilm naqd al-sunnah). I have translated the work in summarized fashion, omitting quotes and details which may not be necessary for someone exploring this meta-aspect of hadith criticism for the first time. Those interested in further details and the primary sources quoted by the author should refer to the original work.

Introduction

While the vastness of scholarly efforts in service of the Sunnah is undoubted, one may think that significant effort, in and of itself, is not an indication of the soundness of methodology. This objection is valid in a sense. However, the reason for highlighting the significant size of the literature is to indicate the magnitude of the task at hand when setting out to evaluate the soundness of such a methodology. This is why I have set out to compose this work after spending thirty years in research and focused specialization in the sciences related to the Sunnah.

I took it as my duty to lay out this logical framework and the assumptions upon which the principles of hadith criticism are built.2 Laying out this framework clearly has three main benefits:

It allows one to move from mere memorization and transmission of these principles to deeply comprehending the methodology of the hadith scholars.

It is the only thing that ensures that the application of these principles is methodologically sound and coherent.

It provides the evidence to conceptualize the methodological soundness (ʿilmiyyah) of this framework of criticism. Without this, a researcher will end up building their conception of the sciences on a composite of various gut feelings, all susceptible to subjectivity.

The main purpose of this paper is to re-frame (iʿādat naẓar) the critical method of the hadith sciences from a rationally identifiable foundation, just as it was framed at the onset of the development of these sciences.

If we want to investigate and verify the objectivity of the principles underlying any science, we ought to ask: are these principles based on sound first principles, or are they based on subjective perspectives that have no real connection between them? There are two ways in which such an investigation can be approached:

The Extrinsic Approach: we can study aspects outside the principles themselves, e.g., are these principles agreed upon by all scholars, or are they differed upon? The extrinsic approach is undoubtedly beneficial; however, this approach is reliant on a rhetorical (khiṭābī) approach and vulnerable to objections. This is because we essentially end up defining something by understanding other things, similar to a person trying to understand what a fire is, not by looking at a fire, but by looking at something that is burned.

The Intrinsic Approach: Alternatively, we can turn to the principles themselves and consider whether they are sound. This is the more robust approach to investigating principles.

The second approach requires awareness of all the principles of hadith criticism and their underlying wisdoms. This is what I have attempted to undertake in this work, hoping to provide an answer to the following question: Were the critical principles used by the scholars of hadith built upon a sound rational foundation?

Chapter 1: Logical Reasons for Rejecting a Report

The Prophetic Sunnah, in its essence, is a collection of reports [like other historical or news reports], which are transmitted from generation to generation. It is thus necessary for the principles of authenticating hadith to be the same rational principles used to authenticate any type of report. The only difference between general rational principles of authentication and the specific principles of hadith authentication will be in the details of implementation.

Before diving into the principles of hadith authentication, we should first discuss the rational principles that are used to authenticate or reject any report.

Intelligent people only accept a report if they believe that this report matches reality. This allows us to define in simple terms what it means to “accept” a report, i.e., believing that it corresponds to reality, and what it means to “reject” a report, i.e., believing that it is contrary to reality.

Since the vehicle of transmission is the people who passed on the information, what determines the correspondence, or lack thereof, between the report and reality is those transmitters. The reality that took place in the past has no bearing on whether the report is true or not. The people describing the event will now either describe it correctly or not.

If we consider what could cause narrators to transmit something which does not match reality, we will find that there are only two possible reasons:

Either someone is intentionally reporting contrary to reality, i.e., lying about it.

Or someone is unintentionally reporting contrary to reality, i.e., they made an error.

Additionally, if these two causes are the only two rational logical causes for rejecting a report, any additional condition placed on accepting reports will be counterproductive, and will result in rejecting acceptable reports. The consequences of not believing a true report could be just as dire as the consequences of believing a false one.

With all of this in mind, we can now classify reports into the following logical categories:

Reports where we have clear evidence (burhān) to indicate that they are free of lies and errors. These are reports that are accepted without doubt.

Reports where we have clear evidence (burhān) to indicate that either lies, errors, or both can be found in it. These are reports that are rejected without doubt.

Reports where there is no clear evidence either way. These are reports regarding which we must suspend judgment.

This leads us to the main inquiry in this paper: Did the scholars of hadith employ a rational framework in their authentication of Prophetic reports?

Chapter 2: The Connection between the Stipulations for an Authenticated Report and the Logical Framework for Report Criticism

We now turn to understanding the five stipulations required by the scholars of hadith for a unanimously authenticated (al-ṣaḥīḥ al-mujmaʿ ʿalā ṣiḥḥatih) hadith:

The uprightness (ʿadālah) of all the narrators in the chain.

The precision (ḍabṭ) of all the narrators in the chain.

Connectedness of the chain (ittiṣāl al-sanad), such that each narrator received the hadith from the previous narrator in the chain through one of the means of reception (ṭuruq al-taḥammul) that allow the narrator to transmit the hadith properly to the next narrator in the chain.

That the hadith is free of defects (ʿilal) that would necessitate rejection.

That the hadith is free of anomalies (shudhūdh) that would necessitate rejection.

If we can demonstrate that these five conditions were placed as a means to achieve the rational conditions (i.e., freedom from the two cardinal afflictions: lies and errors) then we will have demonstrated the methodological soundness and rationality of the framework of the scholars of hadith.

Stipulation 1: Uprightness

Uprightness (ʿadālah) is defined as an intrinsic characteristic that motivates a person to observe God-consciousness (taqwá) and a sense of honor (murūʾah). It can also be summarized as a deep religiosity (matānat al-diyānah), whereby the person’s conscience prevents them from doing anything contrary to that religiosity, such as lying, in particular regarding the Prophet ﷺ. Thus, the stipulation of an upright narrator is a rationally sound principle used to prevent intentional distortions from entering the report.

A upright person does not lie because lying in the context of the Prophet ﷺ context is a contradiction to their testament of faith. Since this is a foundational value emerging from a person’s belief, it will have a demonstrable impact on their worldview and therefore on their actions.3

An objection may be raised that a person could generally be upright, yet fall into one or two instances of major sins (e.g., lying about the Prophet ﷺ). Are scholars of hadith able to identify this?

If this were to happen, it would lead to one of two possibilities:

This narrator may continue drawing further away from uprightness by engaging in major sins. Such a person will then be identified as a non-upright narrator through the pattern of habits that is now visible to those upright people close to him, who will then feel compelled by their own uprightness to expose the deviance (fisq) of the narrator at hand. Such a person’s true reality not becoming known to the expert scholars of narrator criticism is a distant possibility, which can still be addressed by other means.

This narrator regrets and repents from their sin(s). If their major sin was lying about the Prophet ﷺ, their repentance will not be accepted until they identify and confess which narrations they fabricated, dissociating any incorrect passages from being transmitted from the Prophet ﷺ. Such a person’s fabrication will be distinguishable from their truth. As such, this narrator will now be permanently stripped of their uprightness and be deemed a non-upright narrator, even if their repentance is accepted in the Court of Allah.4

In sum, a person who lies even once regarding the Prophet ﷺ will either be exposed due to their non-uprightness becoming well-known, or by their own admission. That said, the discussion here is regarding whether the theoretical stipulations set by the scholars of hadith, if implemented fully and accurately, remove the risk of distortion entering the report (at the level of predominant assumption). Further, a close analysis of the practical tools and methods of the scholars of hadith will demonstrate that they had a comprehensive and verifiable method of identifying narrator uprightness. Lastly, in the worldly context, all systems of law and justice operate on a practical level using witnesses deemed as reliable, without which the system would cease to mete out justice in an appropriate manner. The system of determining upright narrators is significantly more detailed and nuanced than the systems of identifying reliable witnesses in courts of worldly law, despite said courts using testimony when ruling on cases with consequences as grave as capital punishment, imprisonment, and financial penalty.

After accounting for the previous discussions on identifying narrators who have lied, if there is still a possibility of an intentional distortion being introduced into a report, that possibility is eliminated at the content (matn) criticism stage of analysis. The scholars of hadith would meticulously identify content that was corroborated by several narrators and content found only in the narrations of one individual. Content narrated exclusively by an upright narrator was not automatically authenticated and most such anomalies were rejected, as will be discussed further under stipulation five.5

Stipulation 2: Precision

Precision is defined as the ability to transmit something as it was received, in terms of wording or meaning. After having stipulated uprightness, it is clear that being free of any allegation of lying is not sufficient in ensuring that the report is free of unintentional distortions due to memory lapses, lost notes, etc. Evaluating the precision of a report — in part — entails answering the following questions:

Are there details in the report which require a high level of perception (quwwat al-ḥiss) [for its precise delivery]?

Does understanding the report require a high level of intellectual prowess (quwwat al-dhihn fī al-fahm) or superior memorization (quwwat al-dhihn fī al-ḥifẓ) [for its precise delivery]?

Is it a simple narration that does not require any special characteristics within its narrator [for its precise delivery]?

All of the above serve to highlight the importance of precision as an independent stipulation, necessary for the accurate transmission of a report. Practically, scholars of hadith identified a precise narrator as a narrator whose likelihood of accuracy is higher than his likelihood of error.

In brief, there are two main methods for characterizing the precision of a narrator:

An exhaustive analysis of the narrations transmitted by the narrator (istiqrāʾ ḥadīth al-rāwī): This involves comparing each of their transmissions with other narrators who transmit from the same source, then judging whether this narrator transmitted the narration accurately.

Testing the precision of the narrator by testing their memory or by examining the works authored by the individual.

Even with the two methods outlined above, there is no way to absolutely guarantee that someone has not made an unintentional mistake, as forgetfulness is in the nature of human beings. Rather, the goal is to reach a level of predominant satisfaction (ghalabat al-ẓann/tarjīḥ al-iḥtimāl) that a narrator generally does not make unintentional distortions. This is precisely why the scholars of hadith say that the narration of an upright and precise narrator gives us something that is apparently the truth (al-ḥaqq ẓāhiran), but it is not necessarily the actual truth (al-ḥaqq bāṭinan), i.e., what corresponds to reality, until we support the narration with secondary chains and corroborating evidence (qarāʾin).6 A narration that tells us the apparent truth is sufficient for domains of law and theology that require a lower level of evidentiary strength.

Stipulation 3: Connectedness of the Chain

Connectedness (ittiṣāl) is defined as each narrator having displayed to us the narrator from whom he received the narration, using one of the methods of reception (ṭuruq al-taḥammul) which ensures exactness. This makes it clear that the purpose of connectedness is to know the identities of each of the narrators who were part of the journey of this report. This ensures that no narrator has been dropped from the chain or is unknown in identity or characteristics.

Connectedness of the chain allows us to practically test the two previous conditions of uprightness and precision, because without identifying the individuals involved in the transmission, there is no way of identifying whether the individuals are upright or precise. In other words, the issue with unknown narrators is that their uprightness and precision is unknown. This connects us back to the spirit of the isnād, as the successor (tābiʿī) Ibn Sīrīn (d. 110 AH) said, “This knowledge is part of the religion, so evaluate who you are taking your religion from.” Ibn al-Mubārak (d. 181 AH) adds, “Isnād is part of the religion. If it were not for the isnād, then anyone would say whatever they wanted.”7

Conclusion

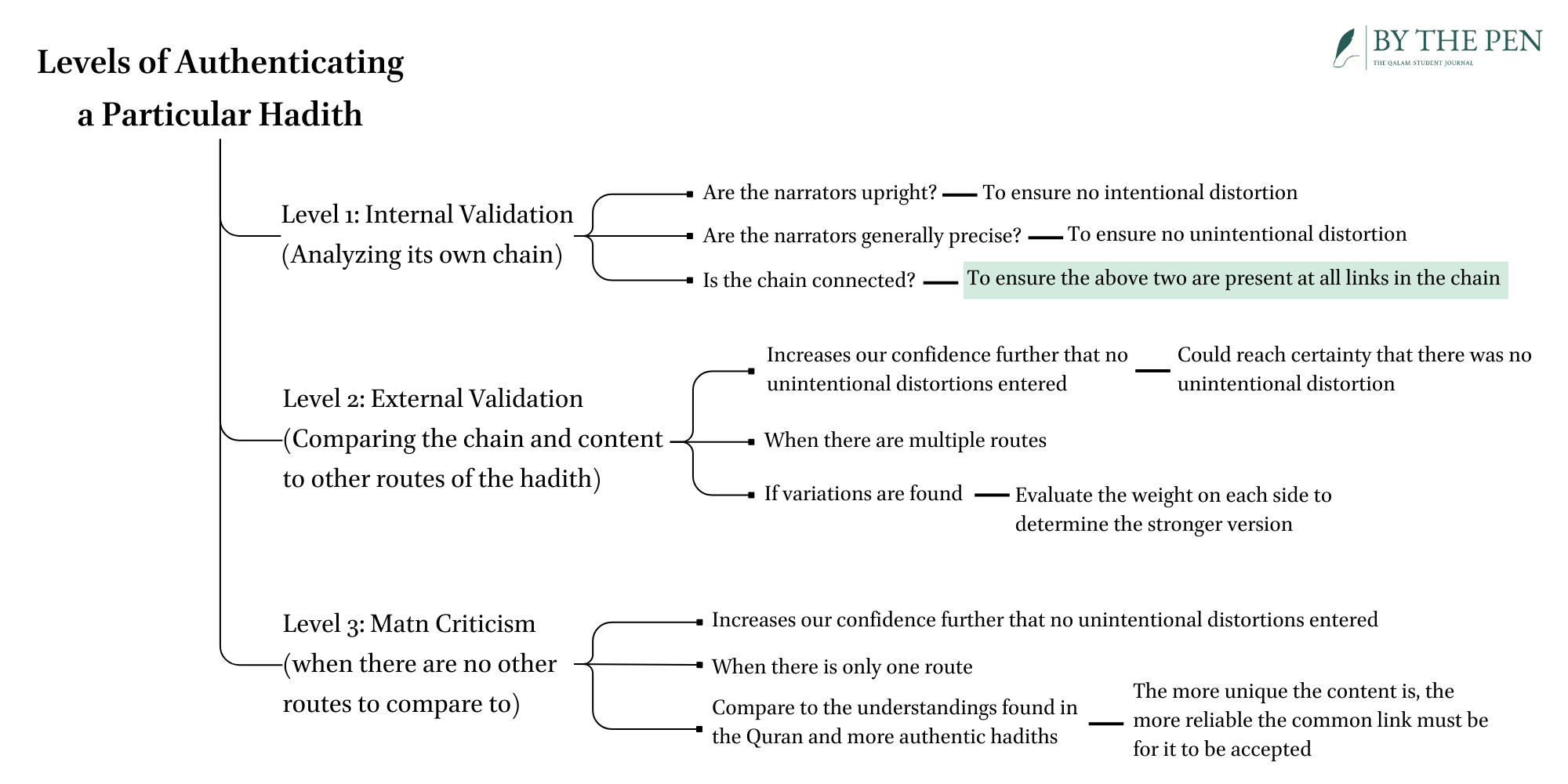

The principles of the scholars of hadith are rationally sound principles which ought to help us objectively arrive at the truth-value of a prophetic report. The five stipulations encompass every rationally-identifiable possibility for distortion being introduced into the report, creating a complete methodological framework capable of identifying which reports are true to reality. Stipulating uprightness (ʿadālah) addresses the issue of intentional distortions and stipulating precision (ḍabṭ) addresses — to a reasonable degree — the concern of unintentional distortions. Having a fully connected chain (ittiṣāl al-sanad) then ensures that these two stipulations are present at every link in the chain. To remove the remaining risk of unintentional errors, being free of defects (ʿadam al-ʿillah) uncovers errors when there are multiple narrators transmitting the same report, while being free of anomalies (ʿadam al-shudhūdh) uncovers errors when there is only a solitary narrator at a particular link in the chain. The last two conditions are discussed in the longer version of this summary.

Figure 1. Three Levels of Authenticating a Hadith

Endnotes

1. Al-ʿAwnī, Al-Shārīf Ḥātim, Al-Usus ʿaqliyya li-ʿilm naqd al-sunna al-nabawiyya. Mawqiʿ al-Shaykh al-Ustādh al-Duktūr al-Sharīf Ḥātim ibn ʿĀrif al-ʿAwnī, https://www.dr-alawni.com/files/books/pdf/1507558275.pdf (Accessed Dec 27, 2024).

2. I use “framework” interchangeably with “principles” (plural) in the translation.

3. The power of foundational beliefs is observable in the many reports of those who willingly sacrificed their wealth and lives in the French Revolution, the American Civil War, and even the Kamikaze during World War II. Belief in something fundamental is the most influential force upon a person’s perspective, worldview and all their decisions. For the believers in the True Religion (Islam), the impact of their belief is even more profound than the impact of false beliefs. This is seen in the countless heroic stories we hear about legendary figures of our history. We can then see rationally that a belief in Allah’s ﷻ watchfulness over us will lead to a person being wary of lying regarding the Prophet ﷺ, just as a rational person will avoid jumping into a burning fire.

4. This harsh measure was to ensure the standards of hadith transmission were kept pristine and pure of all lies. A person who has been known to have lied once has a higher probability of lying again; thus, rejecting all of their narrations is the safest approach. Compare this with the position held by some jurists regarding those who provide false testimony in court even once.

5. The longer version of the summary contains an additional discussion at this point about the narration of a person who is an innovator (mubtadiʿ).

6. This is an elucidation of the difference between certain knowledge (yaqīn) and preponderant knowledge (ghalabat al-ẓann). The first gives us the actual truth and the second gives us something which appears to correspond to the truth, although there is the possibility of some error. However, the apparent truth is still something acted upon by the scholars.

7. The longer version of the summary contains two additional discussions at this point about the two remaining conditions of an authentic report: being free of defects and anomalies.