The Sahāranpūrī Print of the Qurʾan

Mufti Muntasir Zaman

Mawlānā Aḥmad ʿAlī Sahāranpūrī’s (d. 1880) editorial and commentarial work on Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī has undoubtedly cemented his legacy in the annals of hadith scholarship.[1] There is, however, another accomplishment of his that has drawn little attention: his impressive lithographic print of the Qurʾan. To be sure, Sahāranpūrī was not the first, let alone the only, scholar intent on printing the Qurʾan by utilizing the recently available print technology. The Qurʾan was first printed in his home country India in 1802, and subsequently, multiple editorial projects were carried out throughout the nineteenth century.[2] What distinguished Sahāranpūrī’s project was his attention to the accurate orthography of the Qurʾan and the cadre of experts who reviewed his work.

Disheartened by the prevalence of poorly printed muṣḥafs filled with typographical errors and aberrant orthography and encouraged by a merchant friend who had shared his concerns, Sahāranpūrī set out to produce a revised copy of the muṣḥaf in accordance with the ʿUthmānic script (al-rasm al-ʿuthmānī). After its completion, he requested at least twelve senior scholars, including the famed hadith expert ʿAbd al-Ghanī al-Mujaddidī (d. 1879) and Mawlānā Maẓhar Nānotwī (d. 1885), to inspect his work for copyist or printing errors. In their appended endorsements, some of the reviewers mentioned that they closely read the copy multiple times but did not find any errors. The exceptionally aesthetic fifteen-lined muṣḥaf (according to the reading of Ḥafṣ) was lithographically printed by Sahāranpūrī’s Delhi-based publishing house al-Maṭbaʿ al-Aḥmadī in 1852 CE/1268 AH with brief marginal notes. Interestingly, this project was completed prior to the publication of his renowned edition of Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī.[3]

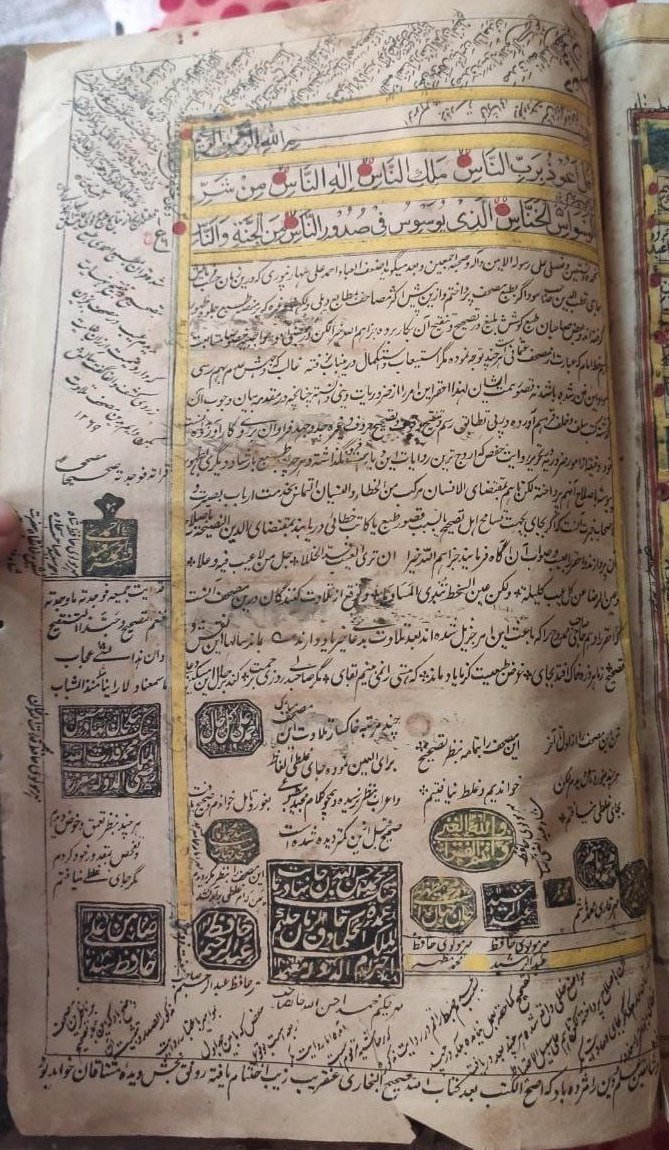

In his marginal and interlinear notes, Sahāranpūrī occasionally mentions alternative Qurʾanic readings, marks places for appropriate pauses (waqf),[4] and adds the number of letters, words, separations, and the regional differences in verse count at the beginning of each chapter.[5] The final page is coated in various colors to indicate the name of a chapter. The lower margins of the verso pages contain catchwords (taʿqība) to indicate the correct sequence of pages. The colophon explains in Persian the context of the project and shares a few words on the review process, the gist of which was summarized above. The endorsement seals are also worthy of note.[6] For instance, ʿAbd al-Ghanī al-Mujaddidī’s seal comprises a single verse, “For Allah is the All-Sufficient (al-Ghanī), and you are the needy ones (Q. 47:38),” playing on the similarity with his name.[7] Sahāranpūrī’s own seal is intriguing. By adding the words “kull ḥāl” after his name (Aḥmad ʿAlī) and omitting the vocalization, the seal can be read as “aḥmadu ʿalā kull ḥāl” (I praise [Allah] in every situation).

Much has been written on the printing of the Qurʾan from the sixteenth century to the present day, yet there is little if any mention of Sahāranpūrī’s edition. The only exception is a few lines written by Mawlānā Nūr al-Ḥasan Kāndhlawī, who is often the only source for valuable information on certain scholars from the subcontinent. Kāndhlawī writes that this muṣḥaf was so well revised that a monetary prize was announced for anyone who could find an error in it. He also states that Sahāranpūrī published muṣḥafs several times, each with distinctive characteristics (e.g., the number of lines).[8] A study of the entire muṣḥaf with particular focus on Sahāranpūrī’s methodology and sources (e.g., Baḥr al-ʿulūm and al-Itqān) would be a welcome contribution. Questions that remain unanswered include: How many copies and subsequent imprints were produced? What impact did this muṣḥaf have on the broader community? One could argue that there is no mention of this project in the relevant sources because it did not receive wide acclaim. While that may be true, there are other documented muṣḥafs with lower critical standards and minimal impact. These and other lines of inquiry can be pursued in a future study.

A Note on the Late Adoption of Print

Notwithstanding textual and orthographic inaccuracy, it appears that Europeans were the first to print the Qurʾan and continued to do so for at least two centuries before the practice made its way to predominantly Muslim lands. By 1538, Paganino de’ Paganini of Venice, Italy had printed the Qurʾan by means of movable type for commercial purposes, but its numerous errors and inaccurate typeface rendered it unacceptable.[9] Throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, muṣḥafs were printed in Europe—often for polemical reasons. In 1786, a copy of the Qurʾan was printed in Russia for which one ʿUmar Ismāʿīl produced the Arabic typeface. In the nineteenth century, the printing of the Qurʾan gained widespread acceptance in other regions, starting in India, then Egypt, Ottoman Turkey, Iran, and beyond. In 1924, a team of experts worked under the auspices of Muḥammad al-Ḥusaynī al-Ḥaddād (d. 1939) for seventeen years to produce “the Cairo edition” or “the King Fuʾād muṣḥaf.” Great pains were taken to ensure its textual and orthographic accuracy.[10] When speaking about “printing” or “the first,” one needs to be careful to distinguish the different types of printing used for these copies (woodblock, moving type, lithographic, etc.). [11]

The late adoption of print in Muslim communities should not be viewed, as is commonly the case, as a sign of intellectual decadence or stunted progress.[12] The claim that the Ottoman sultans banned the printing press is based on an unfounded rumor that began in Europe. Even the idea that the development of a society rests on the success of its printing presses is dubious.[13] One reason for the late adoption of moving type was the lack of an adequate typeface that could accommodate the unique characteristics of the Arabic script. Once lithographic printing became available c. 1796, it was not long before Muslims used it for printing the Qurʾan, as it allowed them to retain the calligraphic aesthetics of their manuscript tradition,[14] not to mention that it was cost effective.[15] Sweeping claims that prior to the advent of modernity Muslim societies en masse experienced an intellectual decline need to be interrogated, as they paint an unfair picture of scholarly activity—particularly when juxtaposed with a professedly enlightened West.[16]

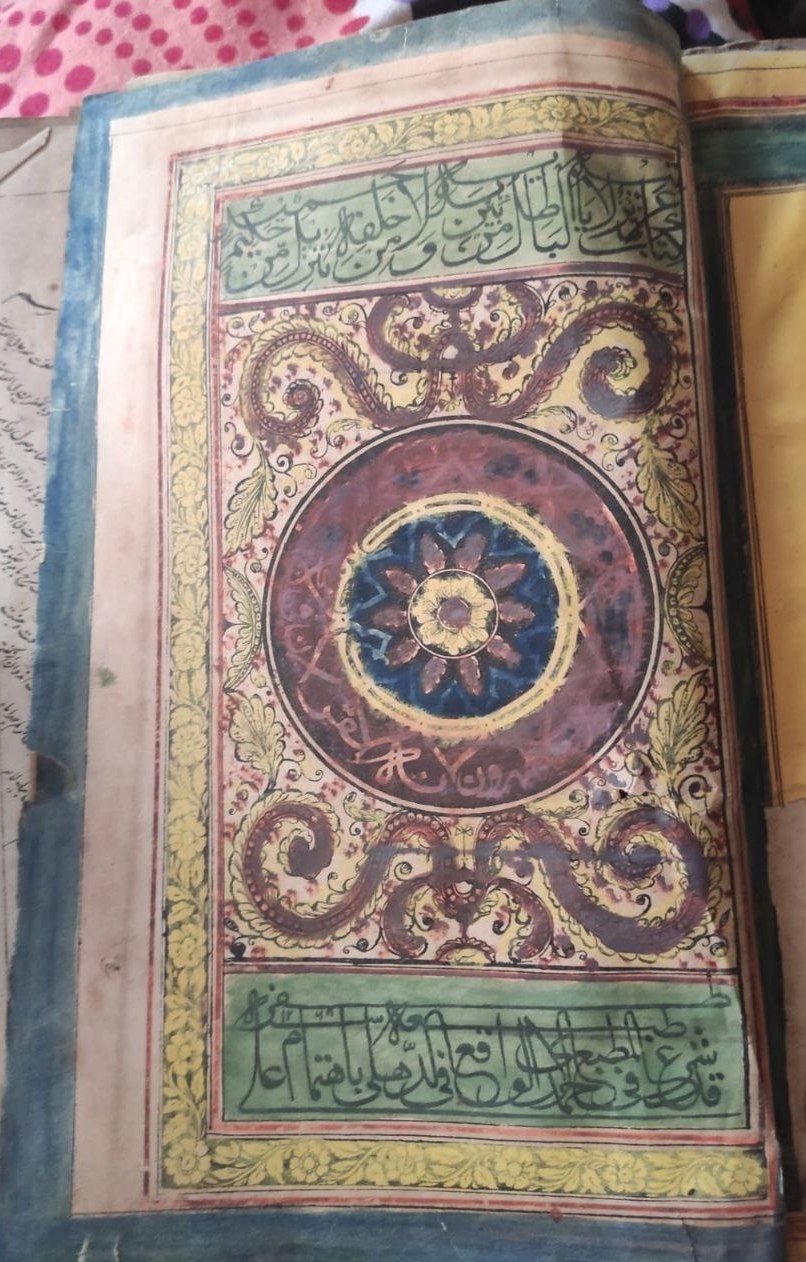

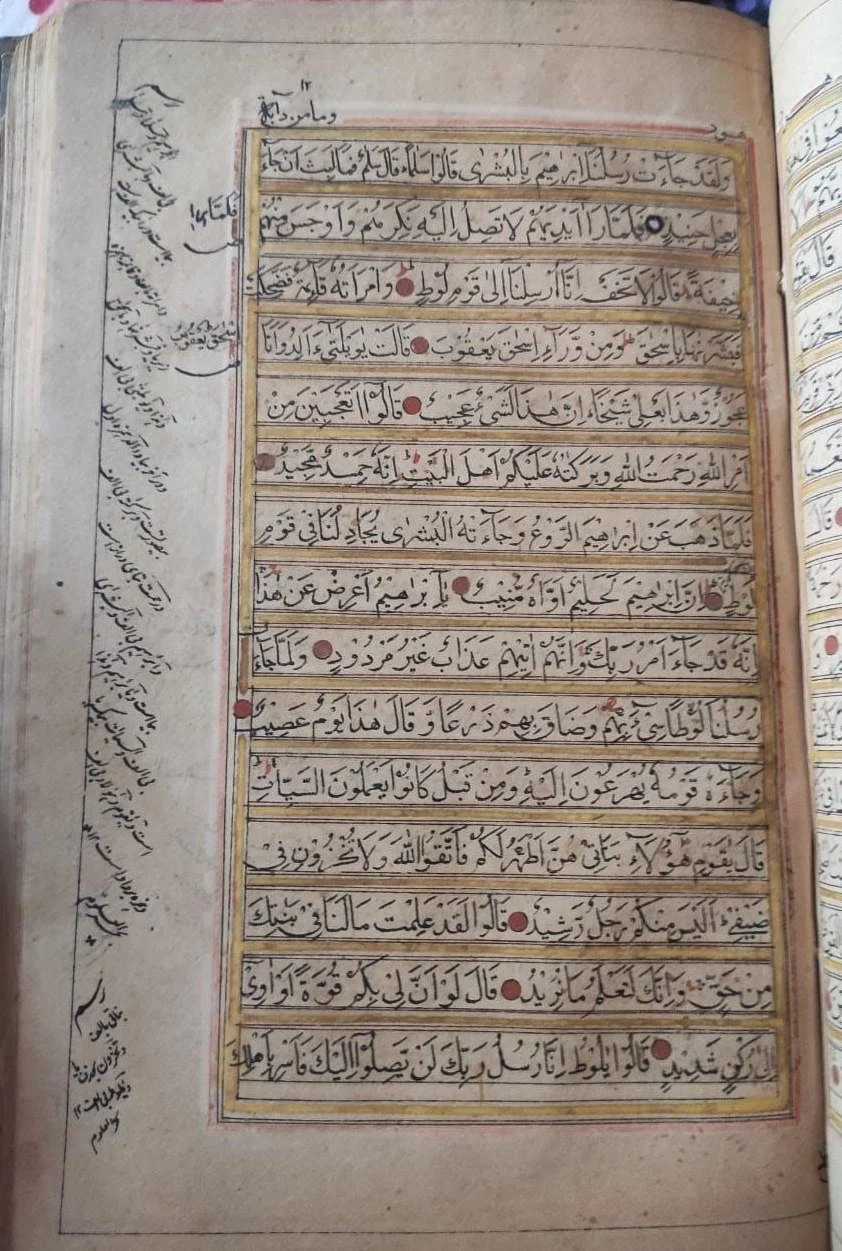

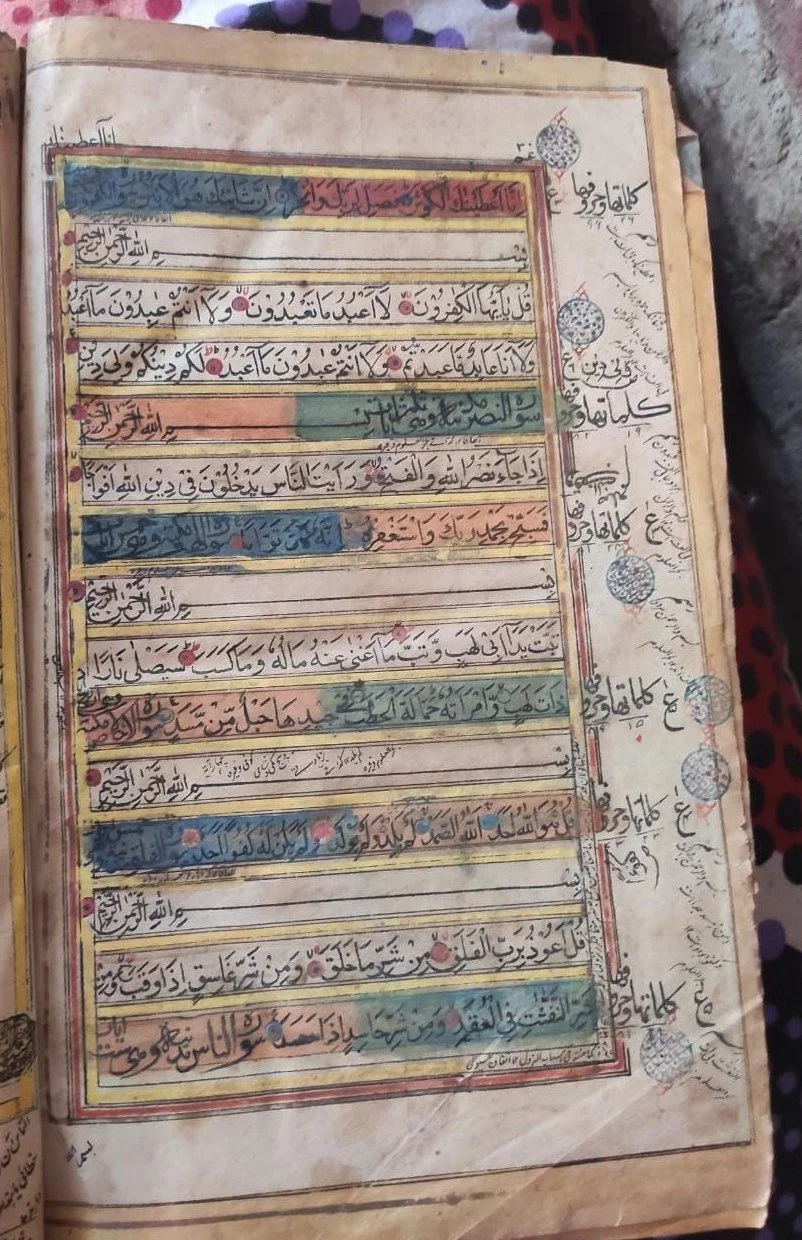

Samples of the Muṣḥaf

A copy of Sahāranpūrī’s muṣḥaf is held in Madrasa ʿAbbāsiyya in Bachraon, India. The following samples were taken from this copy in 2019 and graciously shared by Ustādh Saiful Hadi.

FIGURE 1. Front cover and publication information.

FIGURE 2. Q. Hūd 11:69–80.

FIGURE 3. Q. 108–113.

FIGURE 4. Colophon and Endorsement Seals.

[1] See, for instance, Muntasir Zaman, Ḥadīth Scholarship in the Indian Subcontinent: Aḥmad ʿAlī Sahāranpūrī and the Canonical Ḥadīth Literature (Leicester: Qurtuba Books, 2021).

[2] On the printing of muṣḥafs in India, see Ṣāḥib-e ʿĀlam, “Tārīkh ṭibāʿat al-muṣḥaf al-sharīf fī al-Hind” (N.p.: n.d.),” 873–885.

[3] At the ending of the colophon, Sahāranpūrī announced that his edition of the Ṣaḥīḥ would be completed and printed shortly after this project.

[4] On the history and development of recital pauses in the Qurʾan with a particular focus on the prevalent system that was originated by the Ghaznavid exegete and grammarian al-Sajāwandī (d. 560 AH), see Muḥsin Darwīsh, “Editor’s Introduction,” in al-Sajāwandī, Kitāb al-waqf wa-l-ibtidāʾ (Amman: Dār al-Minhāj, 2001), 29–77. Sahāranpūrī appears to have followed al-Sajāwandī’s system. Compare Figure 3 with al-Sajāwandī, 238.

[5] For a study on the count of verses in the Qurʾan, see Muḥammad ʿAbd al-Mālik, ʿInāyāt-e Raḥmān dar ʿadad-e āyāt-e Qurʾān (Dhaka: Markaz al-Daʿwa al-Islāmiyya, 2022).

[6] On the functions of a taqrīẓ (endorsement) with a particular focus on Mamluk Egypt, see Franz Rosenthal, “‘Blurbs’ (Taqrîẓ) from Fourteenth-Century Egypt.” Oriens 27/28 (1981): 177–196.

[7] The practice of inscribing on a seal a Qurʾanic verse bearing one’s name was not uncommon. See Adam Gacek, “Ownership Statements and Seals in Arabic Manuscripts,” Manuscripts of the Middle East 2 (1987): 90.

[8] See Nūr al-Ḥasan Kāndhlawī, “Ḥazrat Mawlānā Aḥmad ʿAlī Muḥadith Sahāranpūrī kī khidimāt-e ḥadīth,” al-Shāriq 11, no.2 (2008): 32. Mawlānā Nūr al-Ḥasan presented a paper in Gujarat on muṣḥafs in India and alludes to Sahāranpūrī’s muṣḥaf, but the paper has yet to be published. Correspondence with Ustādh Saiful Hadi.

[9] Jonathan Bloom, Paper Before Print: The History and Impact of Paper in the Islamic World (Connecticut: Yale University Press, 2001), 220.

[10] After praising the 1924 Cairo edition of the muṣḥaf, the celebrated Qurʾan expert ʿAbd al-Fattāḥ al-Qāḍī notes that it fell short of the ʿUthmānic script in a few places. See ʿAbd al-Fattāḥ al-Qāḍī, Tārīkh al-muṣḥaf al-sharīf (Cairo: Maktabat al-Jundī, n.d.), 59–63.

[11] On the history of the printing of the Qurʾan, see Michael Albin, “Printing of the Qurʾān,” in Encyclopaedia of the Qurʾān.

[12] For a brief overview of Muslim regions that printed muṣḥafs, see Yūsuf Sarkīs, Muʿjam al-maṭbūʿāt al-ʿArabiyya wa-l-Muʿarraba (Cairo: Maṭbaʿat Sarkīs, 1928), 2:1499–1501.

[13] For more details on this subject, see Kathryn Schwartz, “Did Ottoman Sultans Ban Print?,” Book History 20 (2017): 5–27; Ahmed El Shamsy, Rediscovering the Islamic Classics (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2020), 63–65.

[14] Bloom, Paper Before Print, 224.

[15] Albin, “Printing of the Qurʾān”; Ṣāḥib-e ʿAlam, “Tārīkh ṭibāʿat,” 878.

[16] On the vibrant intellectual activity in Ottoman lands during the seventeenth century, see Khaled El-Rouayheb, Islamic Intellectual History in the Seventeenth Century: Scholarly Currents in the Ottoman Empire and the Maghreb (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015). By examining the works of scholars in the Ottoman Empire and North Africa, El-Rouayheb argues against the notion that the seventeenth century was a period of intellectual stagnation in the Muslim world, as it risks enforcing “the impression that on the one side of the Mediterranean in the seventeenth century one encounters Galileo, Kepler, Bacon, Newton, Descartes, Malebranche, Spinoza, Locke, and Leibniz, whereas on the other side one encounters popular chroniclers, Sufi diarists, popularizers of medical or occult knowledge, and the like.”